It Pays To Be Social

Social skills are driving wage growth and job security in the modern economy. We explore new economic research on why human connection now outperforms technical skill.

Why social skills are becoming the most valuable currency in the modern economy

For years, we were told the future belonged to coders, engineers, and anyone who could speak fluently in numbers. Logic suggested that as technology advanced, technical ability would become the defining advantage. But new economic research tells a more nuanced story. In the modern labour market, the most valuable skill may not be technical expertise at all. It may be the ability to work with other people.

Research from the National Bureau of Economic Research reveals a clear and accelerating trend. Jobs that depend on social interaction, collaboration, and communication are growing faster than those that rely on technical skill alone. In short, it pays to be social.

The quiet rise of social skills

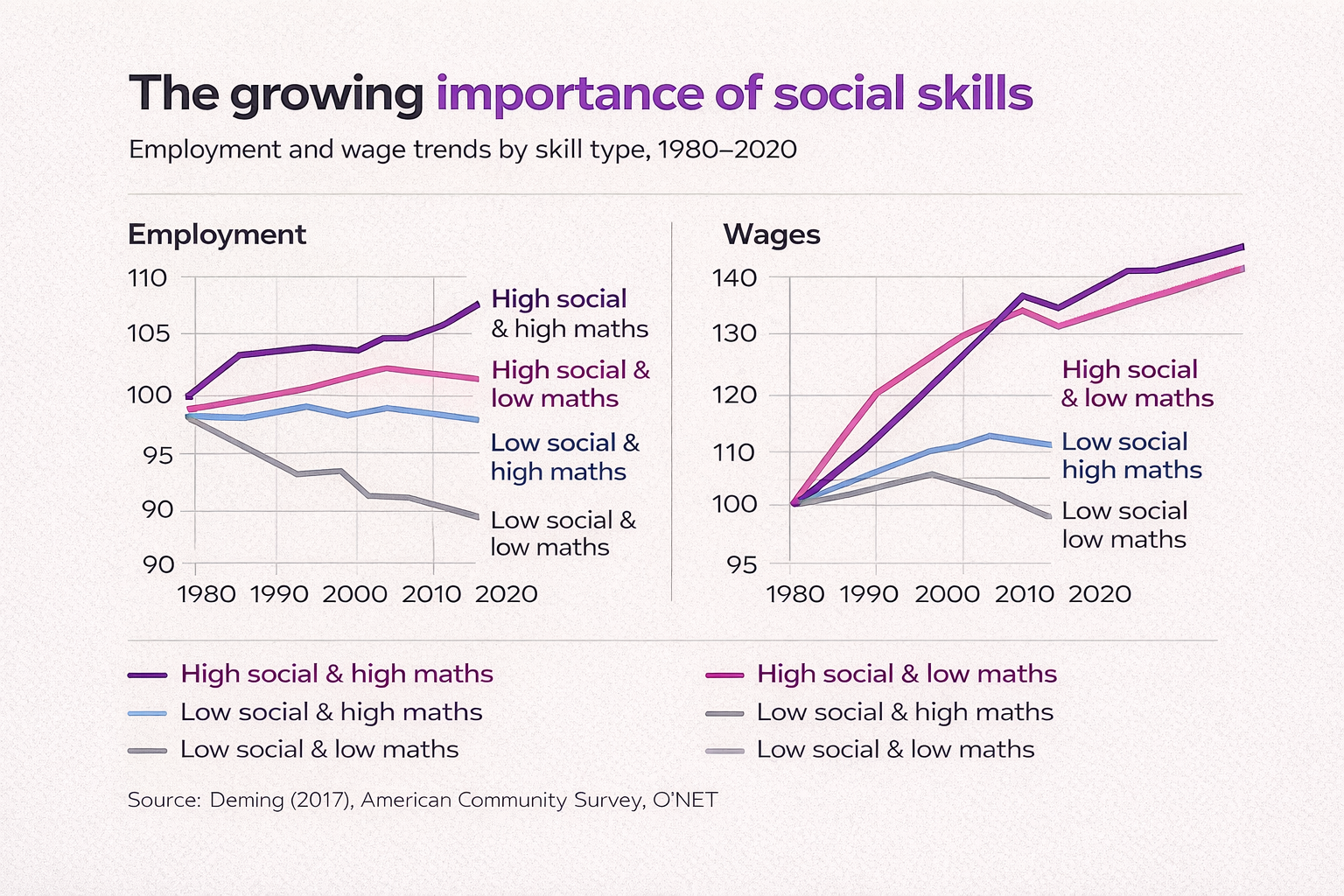

Economist David J. Deming analysed decades of labour market data to understand how job requirements have shifted over time. His findings are striking. Between 1980 and 2012, occupations requiring strong social skills increased their share of the workforce by nearly twelve percentage points. During the same period, many roles that were highly technical but low in social interaction declined.

This runs counter to the popular narrative that automation simply rewards hard technical skill. Instead, the strongest wage growth appeared in roles that combined cognitive ability with social fluency. Jobs that demanded teamwork, persuasion, and human judgment consistently outperformed those focused on solitary or routine technical tasks.

The implication is clear. The modern economy increasingly rewards people who can think and connect at the same time.

Why machines struggle with people

Computers excel at tasks that follow clear rules. They calculate faster than humans, store more information, and optimise systems at extraordinary scale. But social interaction does not operate by fixed rules. It relies on context, emotion, interpretation, and adaptability.

Social skills include things like reading a room, resolving conflict, negotiating priorities, and collaborating under uncertainty. These abilities are deeply human. They draw on tacit knowledge that is difficult to formalise or automate.

Deming’s research highlights the role of what economists call team production. In most modern workplaces, value is created collectively rather than individually. Social skills reduce friction within teams, allowing people to specialise, coordinate, and solve complex problems together. When communication improves, productivity rises.

This is why roles that sit at the intersection of people and problem solving are so resilient in the face of automation.

Collaboration is an economic advantage

As work becomes more interconnected, the ability to collaborate effectively is no longer optional. It is a core driver of performance.

Organisations today rely on cross functional teams, rapid decision making, and constant adaptation. In this environment, technical skill without social competence can become a bottleneck. The people who thrive are those who can translate ideas, align incentives, and move groups forward.

Deming’s research suggests that social skills act as an economic multiplier. They make other skills more valuable by enabling them to be used in combination with others. A technically brilliant individual can only go so far alone. A socially fluent team can compound its impact.

What this means for the future of work

The growing importance of social skills has profound implications for how we think about careers, education, and value.

First, social intelligence offers long term resilience. As routine tasks are automated, roles that depend on human interaction remain difficult to replace.

Second, the highest returns go to people who combine analytical ability with interpersonal skill. The future belongs neither to pure technologists nor pure communicators, but to those who can bridge both worlds.

Third, many education systems still undervalue these skills. Teamwork, negotiation, and communication are often treated as secondary, despite being among the most in demand capabilities in the labour market.

Social skills as cultural capital

At Truffle Culture, we are interested in the forces shaping not just economies, but identities. This research reframes social skills as a form of cultural capital. They are not soft extras or personality traits. They are strategic assets in an economy defined by complexity and change. In a world increasingly shaped by machines, the human advantage lies elsewhere. It lies in our ability to understand one another, collaborate across difference, and create meaning together. That is not just good for society. It is good economics.